Mirtha Dermisache died in January 2012. In her will, she had named heirs and an executor, specifically her friend and student Leonor Cantarelli. Cantarelli, along with Alejandro Larumbe— Dermisache’s nephew and heir, and representative of his brothers, Gabriel, Pablo, and Facundo Larumbe—and Félix Matarazzo—her godson—created the Mirtha Dermisache Archive (AMD, for the acronym in Spanish) to continue to communicate her work and to keep her legacy alive.

At that point, a professional team was put together to catalogue her works and to organize documentary materials. The contents of the archive were classified on the basis of the logic and internal order determined by the artist; they served as the chief source of information for her biographical timeline and curriculum vitae. Cintia Mezza (coordinator of the AMD), and Cecilia Iida and Ana Raviña (its custodians) wrote the biographical timeline that follows in a process that entailed crosschecking information in different materials in the archive, that is, various curriculum vitae, inventories of works, and records of sale written by Mirtha, as well as other documents and audiovisual materials from over the course of her career that had been carefully kept (correspondence, photographs, articles in the press, interviews, texts, prologues to catalogues and books, her methodological writings for workshops, topics from her personal library, and other meaningful objects discovered in the process of taking apart her home-studio).

We propose an active reading of this timeline, one that makes use of some of the resources Mirtha herself employed in her workshops. Music was a key part of her exploration and personal creative process, and she used it as a tool in her original teaching method. She would design a playlist for each activity and technique in the workshops, or she would play music brought in by students; other times, work would be performed in a pregnant silence. The timeline includes a series of songs and albums from the AMD envisioned to be played while reading about different episodes in her life or phases of her work. Another resource is the artist’s own words, which are highlighted.

All of the images in this timeline belong to the Archivo Mirtha Dermisache, and further information on solo and group shows, publications, and works in collections, is available at its website.

We would like to thank the entire AMD staff, the individuals interviewed, as well as researchers Olga Martínez, Natalia March, and Fernando Davis for their contributions to this text.

1940-1966Learning to unlearn

Musical selection for this episode

Milton Nascimento, Travessia, 1967

Leonard Cohen, “Winter Lady,” Leonard Cohen’s Songs, 1967

Deep Purple, The Book of Taliesyn, 1968

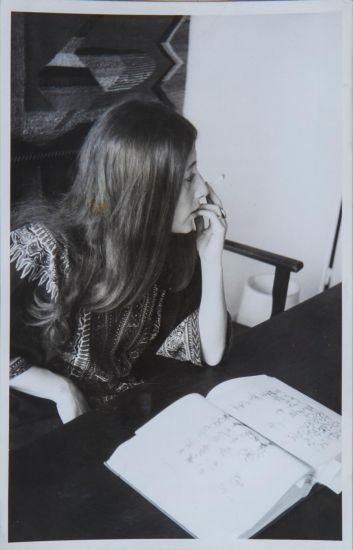

Mirtha Dermisache1 was born on February 16, 1940 in Lanús, a town on the outskirts of Buenos Aires. Her father, José María Dermisache, was a wool and leather merchant who played the accordion; her mother, Filomena Mattera, a pianist who took care of Mirtha and her sister, Beatriz, while also exploring canvas-based crafts and painting.

Restless yet very reserved, Mirtha attended the Colegio San José in Quilmes; she went on to get a teaching degree from the Escuela Normal Nacional Almirante Brown, and then a degree in art education from the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes Manuel Belgrano. She then attended the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes Prilidiano Pueyrredón, currently the Departamento de Artes Visuales of the Universidad Nacional de las Artes (UNA). At the same time, she took studio classes at the Escuela Superior Ernesto de la Cárcova. From the time she was seventeen, she formed part of the Subcomisión de Teatros de Títeres, a group coordinated by the Asociación Gente del Arte de Avellaneda. She was asked to organize a puppet theater that would be used for performances at that association and other organizations, social clubs, and public hospitals.

In 1958, she published an article on painter Ernesto de la Cárcova in the quarterly journal Vuelo, put out by the Asociación Gente del Arte de Avellaneda. Two years later, she began teaching art at public schools in Bernal, Lanús, and Quilmes—towns to the south of Buenos Aires. In 1968, she enrolled in the Instituto Nere-Echea (Basque for “our home”), founded by, among others, Susana Fortunato. A pioneering institution in a conception of education as means of individual and social development, the Instituto Nere-Echea was the first school in Argentina to implement a curriculum based on philosophy for children and “educational camping trips.” The underlying principle was “learning by doing.” Mirtha worked as a consultant in visual education at that school for four years; she developed mural projects with students based on their interests. In the schoolyard, there is still a fountain that she and students made and donated to the school. The production of the cement and stone fountain covered in mosaics of recycled tiles was an enriching experience 2, and the origin, for Mirtha, of a question: Why can children learn by doing whereas, if adults sign up for a studio class, they are “taught” how to draw or paint with antipedagogical methods like copying? In that question lies the basis for the pedagogical vision the artist developed, an approach aimed at unleashing adults’ creative capacity influenced by the writings of Herbert Read and the Sunnyhill experience 2. Revolutionary at the time, her method would lead, a few years later, to the talleres de Acciones Creativas (Creative Actions Workshops) (1972), and then to the public Jornadas del Color y de la Forma (Intensive Work Sessions in Color and Form) (1975–1981) 4.

Mirtha was a member of the cast of Ultra Zum!!, 15 hechos en un solo acto, a play by Celia Barbosa performed at the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella’s Centro de Experimentación Audiovisual from September 16 to 22, 1965. The playbill, which featured an introduction by Roberto Villanueva, explained the experimental work’s primary characteristics:

Here, a group of very young people with backgrounds in dance, film, music, and the visual arts has produced a work that attempts to be different and current, a work at the boundaries of all those disciplines, one that makes use of all their techniques … It encompasses parody of “serious” dance and theater, the creation of objects and audiovisual pieces, references to fashion shows, happening-like staging, allusions to Hollywood stars like Buster Keaton and to folktales like Little Red Riding Hood, classical compositions by Vivaldi to talk about birth-control pills, a tribute to the Beatles and a call for psychedelia, in order to embellish “with all the imagination” that the viewer can muster… 5

While the performances were diverse, they did “share a common repertoire of themes and procedures, as well as an aesthetic and cultural sensibility. The Instituto Di Tella continued to support experimental work of this sort throughout the decade.”6

On those years at the Instituto Di Tella, Mirtha stated:

It’s true, that was my favorite place. Not only because of the exhibitions held there, but because of all the other activities as well, the experiments in theater, music, and dance, and the Escuela de Altos Estudios Musicales. I took part in some of them.7

From 1965 to 1967, she studied philosophy, and in 1968 and 1969 she traveled to Europe and Africa for several months. It was there that her art underwent a transformation, changing from scribbles and disordered drawings to graphisms more like some recognizable form of writing. Regarding that process, Mirtha remarked:

…I never painted or drew, but I did study drawing and painting, as well as printmaking and art history. And whatever I didn’t learn at art school, I was going to learn elsewhere… What did I do with everything I learned? It helped me a great deal to go against the grain, to connect all of those parts within me and, one day, to sit down to write, to unlearn.8

According to Julia Pomiés, “Mirtha Dermisache was between the ages of twenty and thirty when she married Carlos Donnelly; they split and weren’t together during her thirties and forties. In her fifties, they remarried.”9 Neither her relatives nor her students remember exactly when those weddings were held, but everyone agrees that both were celebrated in Uruguay. Carlos, whom everyone called Sonny 10, was an engineer. He was her life companion, and he helped with the coordination and organization of the workshops and studio classes.

Notes

1 Her full name was Mirtha Noemí Dermisache, but she never used Noemí, a name she didn’t like.

2 See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CHyrQjNjSCA

3 Sunnyhill was a pioneering school in liberal education. It was created in 1950 by Alexander Sutherland Neill, a progress Scottish educator dissatisfied with conventional British public education. Mirtha Dermisache’s library contains many volumes on progressive art education for children. For further information, see the AMD.

4 In an interview by the AMD staff with Leonor Cantarelli and Jorge Luis Giacosa (2015) reveals that Susana Fortunato was one of Mirtha’s assiduous collaborators; she was in charge of overseeing the Jornadas del Color y de la Forma.

5 Villanueva, Roberto, “Un experimento”, in Ultra Zum!! (playbill), Centro de Experimentación Audiovisual, Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, Buenos Aires, September 1965.

6 For further information, see Pinta, María Fernanda, “Pop! La puesta en escena de nuestro ‘folklore urbano’,” in Caiana journal, no. 4, first semester, 2014 (http://caiana.caia.org.ar/template/caiana.php?pag=articles/article_2.php&obj=139&vol=4).

7 Quoted in Rimmaudo, Annalisa and Lamoni, Giulia, “Entrevista a Mirtha Dermisache,” in Mirtha Dermisache. Publicaciones y dispositivos editoriales (exh. cat.), Buenos Aires, Pabellón de las Bellas Artes de la Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina (UCA), 2011, p. 8.

8 Quoted in Pomiés, Julia, “Mirtha Dermisache. El mensaje es la acción,” Uno Mismo magazine, Buenos Aires, no. 105, March 1992, p. 49.

9 Ibid., p. 51.

10 Carlos was of Irish descent, and his family nickname was Sonny.

1967-1974From the scribble to writing degree zero and from Lanús to the world

Musical selection for this episode

Astor Piazzolla / Horacio Ferrer, Balada para un loco, 1969

Robert Fripp, Prelude: Song of the Gulls, 1971

Naná Vasconcelos / Agustín Pereyra Lucena,

El increíble Naná con Agustín Pereyra Lucena, 1971

In 1967, Mirtha organized her graphisms in book format for the first time. In an interview with the artist by Edgardo Cozarinsky published in Panorama magazine in 1970,11 Mirtha recounts how she created one of her founding works, Libro Nº 1 [Book No. 1]:

I had studied art, as well as philosophy, for one year, and I was traveling. One day, I felt a sort of knot coming undone in me, the beginning of a process that I could not yet really make out. Sitting in a patio three days later, I started to make scribbles on a piece of kraft paper, like tangles of wool, but with titles and distinct paragraphs. Then letters in earnest. Then I decided [those pages] had to be in a book with arbitrary—though deliberately chosen—size and volume… I wanted them to be pages of a book, an object with front and back cover, bound on one side and open on the other. If someone wanted to stick one of the pages to the wall, they would have to break it, to perform the act of tearing a page out of a book and putting it elsewhere.12

The AMD has records of three books produced in 1967.13 Starting then, Mirtha numbered her books consecutively, beginning each year with number one. She made series of books until 1978, and then again in the nineties. The graphisms don’t make reference to a real alphabet; her technique, generally speaking, entailed different inks on paper, and her aim was always to publish them, to increase their number, to disseminate them. Jorge Romero Brest called her work “a white fly”14 because so unique at the time. Interested in Libro Nº 1, he put Mirtha in touch with Paidós publishers to embark on the publication of that book—a project that ultimately did not come to fruition because of the complications of producing a five-hundred-page-long edition of this sort.

At the recommendation of Carlos Espartaco,15 Mirtha divided the book into two parts to work around the problem of length; one of them—known now as Libro Nº 1, 1967—had brown leather front and back cover, and the other— Libro Nº 2, also from 1967—had hard white front and back cover. A third edition, this one unpublished and unbound, is in the AMD (it follows the same sequence). At least three books were produced in 1968, four in 1969, and eight in 1970—the year when she began using specific writing formats in her work, formats like “text,” “letter,” and “sentence.”

In 1971, she began participating regularly in exhibitions and other projects, that is, she became an active member of the contemporary art scene. There are records of eleven books produced that year. In February, she was invited to take part in the group show From Figuration Art to Systems Art in Argentina, CAyC (Centro de Arte y Comunicación), organized by Jorge Glusberg and held at the Camden Arts Centre in London; she exhibited books. In July, she participated in Arte de sistemas I held at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, also curated by Glusberg, where she showed books produced from 1967 to 1970, as well as fourteen letters from 1970. In the catalogue, she published, in ten languages, a sort of classified ad looking for an editor:

I use this space to say: my work needs a printer.

Mirtha Dermisache. Write to: Juncal 2280 - 9°B,

Buenos Aires, República Argentina

Regarding her books and her determination to publish them to make them available to a broad public for daily engagement, she wrote:

I would exhibit the original [books] and the audience would be able to touch them (the pages were protected) ... It was important that people be able to touch and handle the work. I don’t really care about the shows as much as about publishing the work. 16

In December, pursuant to an invitation from Glusberg to participate in a “laboratory studio,” the Grupo de los Trece was formed17. A text handwritten by Mirtha at the time attests to the fact that she was one of the group’s original members. In it, she remarked:

I’m not sure what this group is supposed to be like. I’m not sure what its aims should be, or why I am part of it. I am sure that it excites me… and I will stay on as long as I feel I play an active part.18

Due to three major developments, her career changed course in late 1971: she created a studio space to stimulate creativity in adults, thus beginning a new phase in her work as an educator19; she applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship, which required developing an extensive project; and she began corresponding with Roland Barthes,20 who proved key to the distinctive nature that Mirtha’s graphisms were taking on.

The taller de Acciones Creativas (tAC) first operated in the artist’s apartment on Juncal Street, in the Barrio Norte section of the city. A larger space later proved necessary and, along with a group of students, she purchased a space at 1209 Posadas Street. It was there that the “taller de Acciones Creativas, de Mirtha Dermisache y otros” was started. The aim was to interact with, explore, and experience different techniques in order to develop creativity and free graphic expression in adults. A wide range of materials and tools—not all of them conventional for art—were made available for use in group classes. The conception was clear and novel:

After a pilot group of eight or nine people was put together, I started working. I told them, “I’m not going to teach you visual language, but provide you with techniques so that you can gain access to that world, to emotion through work with materials, to what happens within, before language.” That’s how the work began.21

In August and September, she began a series of works that she called “incomprehensible writings”: graphisms reminiscent of mathematical formulas, though obviously invented, laid out horizontally.

On October 5, Mirtha, along with Fernando von Reichenbach and composers José Ramón Maranzano, Gabriel Oliverio Brnčić Isaza, and Ariel Martínez, embarked on a musical experience in relation to her graphic works at the Laboratorio del Centro Latinoamericano de Altos Estudios Musicales (CLAEM), a part of the Instituto Di Tella. The project continued through 1971. In it, the musicians used a “graphic converter” to translate her graphisms into sound. In the words of von Reichenbach:

One day, Mirtha’s graphism turned into sound. We did a strange experiment at the Instituto Di Tella in which we articulated sounds synthesized on the basis of a scroll she had drawn. Since she didn’t know how the device worked, unexpected twists appeared in the sound.22

The AMD contains pieces of heliographic paper with texts that appear to be a sound proposal based on her writings, the results of those experiences.23

Also in 1971, Mirtha engaged in experiments, along with Ricardo Ferraro—an engineer and the director of programmers, engineers, and analysts at the CAyC—in which her graphisms were exposed to the processor of an IBM 1130-16K computer and a Calcomp plotter, which translated them into computerized graphisms that could be printed on paper. It was envisioned as a way to publish Mirtha’s work—and to increase its number—which had always been one of her aims.

Meanwhile, Mirtha engaged in an extensive exchange with filmmaker Hugo Santiago, who—during one of his trips to Paris—had given one of her books to Roland Barthes24. In a letter written in 1971—the first in an epistolary exchange that would continue through 1974—the French semiologist described Mirtha’s production as “illegible writing.” The now-historical letter in which Barthes uses that powerful phrase was repeated and reproduced; it is now fundamental to understanding Dermisache’s work:

I will only say how struck I am not only by the remarkable visual quality of your lines (and that is not a secondary question), but also—indeed mostly—by the extreme intelligence of the theoretical problems around writing that your work tackles. You have managed to produce a certain number of forms that are neither figurative nor abstract, forms that could be called illegible writing, which leads readers to formulate something that is neither a specific message nor a contingent form of expression but, rather, the idea, the essence, of writing.25

Even in one of her last interviews, which Mirtha gave for the catalogue to a solo show in 2011, she recalls how deeply she was affected when she first read the French linguist’s words; he grasped, supported, and championed her work as no one had before:

It was amazing because it was at that point that I understood what I was doing. It was as if he were explaining to me what I was doing. That was very important… The day in 1971 when I got the letter from Roland Barthes—especially when I read the part where he says “You have managed to produce a certain number of forms … that could be called illegible writing”— I felt that, after having said “I write” for so many years, someone was finally, for the first time, calling my work writing. That was so important for me. From then on, of course, I could not for an instant think of anything else.26

It was in response to Barthes’s intense words that, the same night she received the letter (March 28, 1971), she began and completed, working without break, her Libro Nº 3 [Book No. 3]27.

At the same time, she was filling out the long application for the Guggenheim Fellowship, asking critics and fellow artists for essays and letters of recommendation that can now be found in the AMD. Contributors to her application included Carlos Espartaco, Roland Barthes, Diego García Reynoso, Gregorio Klimovsky, Jorge Romero Brest, Fernando von Reichenbach, and Jorge Prelorán. Her project, Investigación y creación de grafismos y su aplicación interdisciplinaria [Investigation and Creation of Graphisms and Their Interdisciplinary Application], proposed exploring the zone between visual communications and art, and developing what she called the boletín informativo [informational bulletin], a writing format new to her work. In her application, Mirtha organized her production for the first time, formulating in writing what it consisted of; she provided a systematic account of materials and examples, and presented ideas about how to grow and to expand into other media with an interdisciplinary approach. As she put it:

What does my work with graphisms consist of? It is not easy for me to provide an explanation based on them. While I began developing graphisms some eight years ago, they were not expressed or produced as such until 1967. At that point, a hard-to-imagine process of evolution and projection set in on an aesthetic, but also on a conceptual, level. Important to my graphisms are not only their continuity, development, relationship, and dynamic, but also their forms and, in some cases, their colors. My work, then, bears relation to graphic arts, visual arts, linguistics, and writing, in terms of the elements that make up the object of my creation as such.

…

These graphisms are original forms. They are “signifiers” with no “signified,” though that does not mean that they could be described as arbitrary. … They serve as support, as “empty structure,” so that the other, the one within, might fill each empty signifier with his own signifieds and build his own story.

…

I “write” (inscribe) my books, which are perfectly illegible, and that tenuous structure of “emptinesses” is filled when the “reader” comes along; it is not until that point that it could be said that what I “write” constitutes a “message” and the “empty signifiers” signs.

…

While, in my practice, what has been and is essential is research in graphisms, I have applied them, along with other creators, in an interdisciplinary fashion … I seek to further their expressive capacity, their ability to generate other types of visual and/or audible manifestations.

…

My research into the cinematographic potential of my graphisms and their expressions might lead to the production of a short film.28

Her project was not selected. The letter she received from the Guggenheim Foundation in June 1972 spoke of “budget cuts” and encouraged her to keep working. Mirtha was upset by the rejection, even though she had done so much over the course of the year: she put together an extensive network of contacts and her work had become known to a number of intellectuals whose sharp vision helped shape a critical apparatus crucial to her own process, to self-recognition in her work, and to confidence in its interdisciplinary potential.

There are records of at least six books produced in 1972; that same year, she made a short series called textos legibles [legible texts], some of them dated 1972 and 1973. She also started work on a series entitled páginas [pages], páginas escritas [written pages] or páginas de un libro [pages of a book], which she would continue to develop for the length of her career, but with particular intensity in the seventies and nineties. Those works consist of writing directly on CAyC letterhead.

On May 12, she participated in the “Encuesta acerca de arte e ideología Jasia Reichhard - Jorge Glusberg” at the CAyC. On September 21, the exhibition Arte e ideología. CAyC al aire libre, curated by Glusberg, opened29. According to a letter from Glusberg to the City of Buenos Aires requesting the use of the plaza space, the original name of the event was Escultura, follaje y ruidos I y II; it was scheduled to open sooner, but the incident known as the Trelew massacre, which occurred on August 22, caused the opening to be postponed and changed the event’s ideological bent. In the exhibition, envisioned as a continuation of the experiences the CAyC had organized in Rubén Darío plaza in 1970, works were made to dialogue in the public space. Mirtha showed her Diario 1 Año 1 [Newspaper 1 Year 1], published by Glusberg for the occasion, as part of the intervention Escenas de la vida cotidiana o La gran orquesta [Scenes from Daily Life or The Great Orchestra] by artist Mederico Faivre, installed in a public bus. Later, the artist described the black rectangle on Diario’s left column as an expression of mourning for those killed in Trelew.

The only time I made reference to the political situation in my country in my work was in Diario: the column on the left on the last page alludes to those killed in Trelew. That was in 1972. Except for that massacre, which affected me—and many others—a great deal, I never wanted my work to be read in political terms. What I was doing, and still do, is develop graphic ideas on writing which, in the end, have little to do with political events but much to do with the structures and forms of language. I never delved into the theory on the topic, though.30

There were a number of later editions of Diario: a second edition by Mirtha Dermisache herself (Buenos Aires, 1973); a third edition by Guy Schraenen éditeur (Antwerp, 1975); a fourth edition (a four-page facsimile) by Silvia de Ambrosini, published in Artinf journal (Buenos Aires, 1995); and a fifth edition by Mirtha Dermisache (Buenos Aires, 1995).

On March 12, 1973, Gregorio Klimovsky published an essay on her work, calling it an intellectual challenge that proposed a method of “open” communication. Klimovsky compared her art to the use of the axiomatic method in modern mathematics and to the construction of a musical line on the basis of sheet music. That same year, Oscar Masotta proposed envisioning Mirtha’s writing as a channel, a medium removed from the message. He explained, “Her art shuts itself off like a stubborn and wild animal in strange terrain. There is, in that stubbornness, a structure that semiologists have not described, one that merits study.”31 Silvia de Ambrosini, director of Artinf journal, wrote the text “Mirtha Dermisache hoy,”32 which marked the beginning of a friendship between the two women that would last for years.

In July, her works were published in the journal Ciencia Nueva33. For that publication, she made printing blocks, matrices, for mass printing akin to a series of pieces she called Reportaje [Interview]. There are records of at least four books produced in 1973, as well as a strange portrait (perhaps a self-portrait) from that same year. She became a member of the CAyC’s Communication Department and attended a number of seminars there, among them “Teoría del signo artístico,” given by Professor Carlos Espartaco, and “Diversas aplicaciones de los modelos lingüísticos” and “El análisis científico de los fenómenos de comunicación,” both given by Armando Levoratti. She was invited to participate in the 12th São Paulo Biennial, though she ultimately did not take part34. She did travel to São Paulo in early 1974, however, giving a lecture entitled “Development of Free Graphic Expression in Adults” at the I Congresso Brasileiro de Educação on January 12.

According to the AMD, she produced at least eight books in 1974, incorporating into her graphic production new formats in works like fragmentos de historias [fragments of stories] and historietas [comic strips], as well as Boletín informativo, a series of large-scale pieces that were part of her proposal for the Guggenheim. This same year, Libro Nº 1, 1969 [Book No. 1, 1969] was published after having been released, in December of the previous year, by Glusberg for the CAyC. She was invited to participate in a number of CAyC activities, publications, and group shows, among them Kunsystem in Latijns-Amerika, organized by the International Cultureel Centrum (ICC) in Antwerp. Latin American Week was held in that city in the framework of the show; it included roundtables, screenings of films, and concerts of electro-acoustic music. On April 24, she took part in the roundtable “Art and Culture in Third World Countries.” The show went on to tour the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels and, under the title Art Systems in Latin America, the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. It was in the context of those shows that Mirtha met Guy Schraenen and Marc Dachy, curators specialized in artists’ books; they took an interest in her production. Along with Guy and his wife, Anne Schraenen, she was invited to participate in the publication Cahier nº 1 [Notebook No. 1], which came out the following year. Guy would become another pillar of her career; he was her first editor in Europe and an adviser to her publications; through him, she learned to pay more careful attention to the materials she used and to the size of print runs.

On September 20, 1974, the exhibition Arte en cambio II opened at the CAyC. Mirtha showed Fragmento de historieta [Fragment of Comic Strip]. From November 28 to December 6, her work was on exhibit in Latin American Week in London, an event held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), Nash House, London.

In December, Carmen Waugh gallery in Buenos Aires made its space available to Mirtha for a show of students’ work. Mirtha was not sure whether or not to accept the offer, since her studio was not geared to training artists but to fostering creative freedom in adults. Ultimately, she decided to organize an extension of the tAC in the gallery, offering classes to the general public free of charge. The experience was, in a sense, a pilot that gave rise to the Jornadas del Color y de la Forma. The posters advertising the event read:

Can grown-ups express themselves using the techniques children use?

We believe they can.

We will do it all together.35

Notes

11 Cozarinsky, Edgardo, “Un grado cero de la escritura,” Panorama magazine, Buenos Aires, year VII, no. 156, April 1970, p. 51. The title makes reference to the concept of writing Roland Barthes develops in his first essay, Le Degré zéro de l’écriture (1953).

12 Ibid., p. 51.

13 As explained later in this episode, the artist herself divided a single 500-page edition into these three parts.

14 Romero Brest, Jorge, “Una mosca blanca,” Crisis, Buenos Aires, no. 27, July 1975, pp. 74–75.

15 According to her students, Carlos Espartaco might have been the one who gave the artist this piece of advice, but it could also have been Jorge Romero Brest or Jorge Glusberg; there is no written confirmation of this information in the AMD.

16 Mirtha Dermisache, in Rimmaudo, Annalisa and Lamoni, Giulia, op. cit., pp. 10–11.

17 According to a printed CAyC document in the AMD, the original members of the Grupo de los Trece, formed in 1971, were: Jacques Bedel, Luis Benedit, Mirtha Dermisache, Gregorio Dujovny, Jorge Glusberg, Víctor Grippo, Jorge González Mir, Vicente Marotta, Alberto Pellegrino, Alfredo Portillos, Luis Pazos, Juan Carlos Romero, and Julio Teich. That initial group underwent changes and, according to researcher Fernando Davis—consulted for this project—the “laboratory studio” drew inspiration from the ideas of Polish theater director Jerzy Grotowski, who had given an informal lecture at the CAyC. Mirtha had been invited to attend that event; she is on the list of the group’s original members. The main aim of the group was to join thought and production in order to foment systems art of the sort advocated by the CAyC.

18 Handwritten text by Mirtha Dermisache on her expectations regarding participation in the Grupo de los Trece—most of the other members of the group wrote similar texts—, Buenos Aires, December 1971.

19 There are some discrepancies in documents in the AMD about when she began this work; it is sometimes recorded as 1971 and sometimes as 1972.

20 French philosopher, writer, essayist, and semiotician Roland Barthes (1941–1980) is the author of Le Degré zéro de l’écriture, 1953; Éléments de sémiologie, 1965; L’Empire des signes, 1970; and other books that theorize work-text.

21 Pomiés, Julia, op. cit., p. 49.

22 Unpublished essay by Fernando von Reichenbach on Mirtha Dermisache, Buenos Aires, May 11, 1973. There are copies in the AMD and in the von Reichenbach Archive, Universidad Nacional de Quilmes.

23 Cecilia Castro of the von Reichenbach Archive, Universidad Nacional de Quilmes, crosschecked the information in the AMD. After the experiences at the Instituto Di Tella, the CLAEM moved, in 1972, to the Centro Cultural General San Martín, where it formed part of the Centro de Investigaciones en ComunicaciónMasiva, Arte y Tecnología.

24 Through Silvia Sigal, Mirtha and Hugo Santiago engaged an epistolary exchange from 1970 to 1972. In 1972, Santiago gave Barthes a book and letter from Mirtha and, later, her Diario 1 Año 1 [Newspaper 1, Year 1]. That was how Mirtha came into direct contact with the French philosopher.

25 Letter from Roland Barthes, Paris, March 28, 1971.

26 Quoted in Rimmaudo, Annalisa and Lamoni, Giulia, op. cit., p. 8.

27 This information is from an interview by the AMD staff with Olga Martínez, Buenos Aires, November 20, 2016.

28 Mirtha Dermisache’s application for the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, 1971.

29 The show was one in a set of two exhibitions entitled Arte de sistemas II, one held in Rubén Darío plaza and the other at the Museo de Arte Moderno.

30 Rimmaudo, Annalisa and Lamoni, Giulia, op. cit., p. 15.

31 Masotta, Oscar, letter-essay for Mirtha Dermisache, Buenos Aires, March 1973.

32 The final version of the article was published later as “Dermisache. El libro ausente”, Artinf journal, Buenos Aires, no. 91, 1995, pp. 22–23, pursuant to the publication, in the journal’s issue no. 90, of the fourth edition of the Diario 1 Año 1.

33 Ciencia Nueva. Revista de ciencia y tecnología, Buenos Aires, year III, no. 24, July 1973, p. 48.

34 The artists invited decided not to participate, as explained by Glusberg in the article “Por qué resolví participar con Art Systems en la Bienal de San Pablo y ahora desisto.”

35 Poster for the Jornadas del Color y de la Forma, Carmen Waugh gallery, Buenos Aires, December 1974.

1975-1981Write until disappearing...

Musical selection for this episode

John Cage, Empty Words, 1973/1974

Brian Eno, Music for Airports, 1978

Mike Oldfield, Tubular Bells, 1979

The AMD contains a set of Libros de apuntes [Notebooks], as the artist called them, from this period, representative of the work routine she performed throughout her lifetime. According to her family, Mirtha would always carry notebooks of this sort in her bag, working on graphisms on a daily basis.

In 1975, she took part in Art Systems in Latin America, a show held at Espace Cardin in Paris (it later toured to the Institute of Contemporary Art, London) and in Arte de sistemas en Latino América, held at the Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna, Palazzo dei Diamanti, Ferrara. That same year, Cahier nº 1 was published; twenty numbered copies of a print run of one hundred and fifty contained an original work on carbon paper; there were also two artist’s proofs marked A and B. She began working on what she called her cartes postales, a series of works of illegible writing with the dimensions and structure of a postcard. Ulises Carrión published them in a special mail art edition of his monthly Ephemera36.

After the successful experience of the workshop in Carmen Waugh gallery, the tAC, coordinated by Mirtha, organized the first Jornadas del Color y de la Forma on July 4, 5, and 6, 1975; the event took place at the Museo de Arte Moderno, which was housed on the ninth floor of what is now the Teatro San Martín. Free of charge, the sessions were geared to adults, with or without a background in art, interested in experimenting with different techniques. In the space, open to the public from 5 to 8:30 p.m., materials were laid out on large tables. Coordinators—students in Mirtha’s first workshops—explained how to use the materials. The basic instruction was not to pass judgment on the work created. A playful and relaxed atmosphere conducive to creativity was generated.

Mirtha ended the year with a new body of work. She participated in the Paris Biennial and produced the Libro de vidrio [Glass Book] and the Libro de espejo [Mirror Book]. The artist explained:

For a show with Minujín, Peralta Ramos, Grippo, Kennedy, [and] Clorindo Testa…, I decided to make a glass book and a mirror book. Neither one was very long due to questions of structure and fragility. The design, in both cases, was quite classic. The cover [of the glass book] was made of translucent glass, and when people opened it they would find that each page was transparent. And, upon opening the mirror book, the reader would see himself, [and] the setting … Years later, I realized that in that second book I no longer produced even the signifier, perhaps to enable the reader to provide everything. With those last two books, I brought a cycle to a close 37.

In 1976, she gave her first lecture at the II Congresso Brasileiro de Educação Artística in São Paulo. In April, a work of her authorship was published in Luna-Park journal; “Articles for Kontexts by Mirtha Dermisache 1975” appeared in Kontexts Publications, the Netherlands.

From June 15 to 19, the Segundas Jornadas del Color y de la Forma were held, once again at the Museo de Arte Moderno. The slogan for the event was “The museum will be turned into a great workshop of creative activities, for adults only”38. Some participants had taken part in earlier editions; others came at the recommendation of a friend or in response to the posters; still others were curious due to the long lines at the entrance to the venue. Once inside, some only looked on, while others delved into the techniques proposed. The third edition was held in September, at the same place and during the same hours. This time, there were nine large tables, each one with its own coordinator and materials. Hanging on the walls to dry were earlier works as varied in nature as the participants, who grew in number each day.

In June, Mirtha showed work—specifically her glass and mirror books—in the exhibitions Arte en cambio 76 and ¿Hay vanguardia en Latinoamérica? Respuesta argentina, both held at the CAyC; she took part in Text-Sound-Image. Small Press Festival, a show that toured the Netherlands, organized by Guy and Anne Schraenen at the Galerie Kontakt in Antwerp. Starting in November, her work formed part of Zeitungskunst, a group project housed at the Verlaggalerie Leaman, also organized by Guy and Anne Schraenen, and in Newspaper Arts Arts Newspaper at Other Books & So space, a gallery, shop, and—later—archive (Other Books & So Archive, OBASA) in Amsterdam created and run by Ulises Carrión. She formed part of a number of projects related to systems art in European cities; along with Schraenen, she participated in group shows on artists’ books and on other forms related to the specific problem of art and communication, among them Éditions et communications marginales d’Amérique latine, Maison de la Culture, Le Havre. In December, at Artemúltiple gallery, she brought the year to an end with an informal lecture with slide projections on the final Jornadas she had organized in 1976.

In August 1977, the Cuartas Jornadas del Color y de la Forma were held at the Museo de Arte Moderno. The number of participants and coordinators grew. This time, a set of new guidelines were handed out to attendants:

We will not teach you how to draw or how to paint; you won’t learn about art history, composition systems, or art appreciation. All we will do is explain techniques. As children, did those of us who are now adults have access to free graphic expression?

Why is it that when an adult is inclined to graphic expression he must resort to a rational and systematized learning process?

We will release the world of forms locked inside and recognize ourselves in them.

There are no good or bad, pretty or ugly, works in our view; there are different ways of expressing oneself.

We extend our inner gesture in the work tool.

What happens on the page does not matter: what matters is what happens within us 39.

There are records of at least three books of graphisms produced in 1978; her work continued to gain legitimacy on the international scene. She took part in the group show Typographies. Écritures, curated by Christian Dotremont for the Maison de la Culture de Rennes. The show brought together 20th-century artists from a number of different countries, all of whom attempted, in their work, to engage in a sort of writing40. In March 1978, she took part in Tecken. Lettres, Signes, Écritures at Malmö Konsthalle, an exhibition curated by artist Roberto Altmann; in June, Guy Schraenen presented 4 Cartes postales in Belgium, an edition with four original signed copies.

On September 27, 1979, Dermisache, along with Martha Susana Buratovich, Silvia Vollaro, and Jorge Luis Giacosa, registered the trademark “Jornadas del Color y de la Forma” and, first from October 3 to 7 and then from October 9 to 14, the fifth edition of that event was held at the Museo de Artes Plásticas Eduardo Sívori. That edition was sponsored by companies that donated work materials (paint, clay, rags, sponges, ink, paper, and so forth). Around five hundred people participated in each session; they sometimes had to stand in long lines to get in.

From January 9 to 13, 1980, the Primeras Jornadas del Color y de la Forma in the city of Bariloche were held; this was the only edition of the event to take place outside of Buenos Aires. To organize it, members of the tAC traveled to Bariloche beforehand in order to train twenty-five people as coordinators who might later communicate the event. The Jornadas were sponsored by Aerolíneas Argentinas and by the local departments of Tourism and Culture. They took place in an annex of the Centro de Arte Di Tullio. The techniques and implements used included wet sheets of paper, sponges, individual and joint work in clay, murals in tempera paint, carved brick, and black and white and color monotypes. The event was extremely well attended and appreciated by the local community. Leonor Cantarelli recalls:

I was twenty-two years old when I first went to Mirtha’s workshop; it was in 1976, one year before it moved to Posadas Street, where it would eventually have as many as one hundred and thirty students … I was involved in every detail of the organization of the event in Bariloche; we were seen as “apostles”—they even called us that—because Mirtha was extremely demanding at every instance, from the very beginning of the Jornada until it was over … Each step, including choosing the right music for each technique, was carefully heeded. To be an assistant or coordinator required taking a special and taxing course, which meant not only mastering all facets of the technique, but also knowing how to handle the entire situation, from welcoming students or participants to closing the door behind them41.

In 1981, Mirtha continued to participate in a number of Guy Schraenen’s initiatives, among them Libellus, a monthly publication of mail art put out by the ICC in Antwerp. The Sextas Jornadas del Color y de la Forma, organized that same year42, were once again sponsored by Aerolíneas Argentinas. The credits read, “Idea and direction by Mirtha Dermisache” and “Supervision and coordination by Jorge Luis Giacosa.” Giacosa recalls:

At the tAC, we were bound by a mystique, a magic, that later made itself felt on a much larger scale at the Jornadas. The Jornadas—especially the last ones at the Centro Cultural Recoleta, where everything was larger than life—were a celebration. [At Recoleta], there was an eight-ton mound of clay!… The event was a sort of “art nursery school,” where the idea was to play, to have fun with art supplies. The aim was not to turn you into an “artist,” in fact that happened to very few, if any, of the participants. What those of us who had been students and later worked as coordinators did was to facilitate in others the freedom that we ourselves had experienced … There were two truly remarkable things at Mirtha’s studio, where I first went at the age of twenty-five. The first was how time was handled; it was important to be on time so that everyone could start together and be there when the technique was explained; the session usually started out with joint work, but each individual would decide when to leave. As Mirtha put it, “The class comes to an end when each person’s need to express himself comes to an end,” and that could take until midnight. The second key feature was that there was no verbal assessment or analysis of the work produced or instance where participants would share what they had felt—it was purely a question of making. I also learned the endless value of order from the standpoint of coordination—that was central to the Jornadas. For that expansive and free creative work to flow, for that total celebration of color and form to ensue, a seamless structure was required, and all of us who worked behind the scenes—and there were over one hundred and fifty of us—acted as a sort of clock at the service of the other’s expressive freedom—and, at Recoleta, there were so many!39

Thanks to the dimensions of the space, it was possible to include other techniques, such as video (participants were given cameras). They worked with wet sheets of paper, sponges, aniline dye, benzene, black and white and color monotypes, clay in groups and individually, tempera in groups, finger paint, and brick carving. It is estimated that some eighteen thousand people participated; the media covered the event widely. The next year, Mirtha, Lucía Capozzo, and Carlos Donnelly reflected on the experience in an interview in Summa magazine:

There are individual and group techniques, and others, such as carving on brick wall and the clay table, that I would not call group techniques, but rather “summation techniques”: people add their work onto a total work that is created through the addition of all the small—and not so small—individual efforts… The aim of including video was to enable participants to come into contact with that system and to learn to express images in that medium or language… The Jornadas are really a sort of work-revelation whose breadth is limited solely by the creative capacity of each of the individuals that takes part. It’s like tossing seeds. Where they take, the true aim of the Jornadas will bear fruit; I provide the foundations, the materials, and the space for an inner adventure. Each individual responds as he wants, discovering the pleasure of being able to express his true inner self with a piece of clay, on a sheet of paper, or on a wall… When I say work-revelation, I mean that the audience does not come to see a work, but that that audience, working, is the work 44.

Notes

36 Writer, editor, and experimental artist Ulises Carrión (Veracruz, Mexico, 1941 – Amsterdam, 1989) left both Mexico and orthodox literature behind to produce contemporary art in Europe.

37 Pomiés, Julia, op. cit., p. 51.

38 Poster for the Segundas Jornadas del Color y de la Forma, Museo de Arte Moderno, Buenos Aires, June 1976.

39 Guidelines that appeared on the poster for the Cuartas Jornadas del Color y de la Forma, Museo de Arte Moderno, Buenos Aires, August 1977. The conceptual guidelines were formulated in 1975, and they were used for both the Jornadas and the taller de Acciones Creativas.

40 Fellow participants included Guillaume Apollinaire, Roberto Altmann, Frédéric Baal, Roland Barthes, Marcel Broodthaers, André Breton, Documents DADA, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Brion Gysin, Jasper Johns, Henri Lefebvre, El Lissitzky, René Magritte, Sophie Podolski, Henri Matisse, Piet Mondrian, Man Ray, and A. Rodtchenko.

41 Interview by the AMD staff with Leonor Cantarelli, Buenos Aires, October 17, 2015.

42 This edition of the event was held from November 12 to 15, November 19 to 22, and November 26 to 29 at the recently founded Centro Cultural Ciudad de Buenos Aires (today the Centro Cultural Recoleta), where the Museo Sívori was housed. These gatherings came to be known as the “final Jornadas,” not because they were intended to be the last, but because, as former students report, the project did not continue due to lack of funding. The AMD contains correspondence with Nelly Perazzo and with the management of Aerolíneas Argentinas regarding the Séptimas Jornadas, but there is no documentation on why they were never held.

43 Interview by the AMD staff with Jorge Luis Giacosa, Buenos Aires, October 17, 2015.

44 “Mirtha Dermisache,” in Summa. Revista de arquitectura, tecnología y diseño, Buenos Aires, Ediciones Summa S.A., no. 178/179, September 1982, pp. 69–80.

1982-1997A time between times

Musical selection for this episode

Vangelis, Spiral, 1977

Empire Centrafricain, Musique Gbáyá / Chants à penser, 1980

UDU Chant / Mickey Hart, Planet Drum, 1991

On April 29, 1982, the Asociación Civil Taller de Acciones Creativas was founded, and from July 2 to 11 an encounter on the Jornadas del Color y de la Forma was held at the Fundación San Telmo. The event was described as a “multiple and multidisciplinary ‘Color - Form - People - Now’ occasion with screenings, roundtables, and a photography exhibition.”45 The aim of the event at the foundation was to assess the achievements of the Sextas Jornadas. Participants included Jorge Romero Brest, Gregorio Klimovsky, Nelly Perazzo, and Emilio Renart. The debate revolved around whether or not the Jornadas could be considered an artistic event, and whether or not they could be envisioned as a form of knowledge.

The tAC began holding children’s birthday parties in an action that, once again, turned out to be ahead of its time. While Dermisache continued to develop her art and to teach in these years, she did so at a slower pace; she took part in many exhibitions and projects, but put her own production on hold. Those close to her mention her husband’s health problems and sheer exhaustion from the Jornadas as possible reasons.

Over the course of the eighties, she engaged in group projects, like the Muestra internacional de libros de artistas at the Centro Cultural Ciudad de Buenos Aires (1984); Rencontres autour de la revue Luna-Park at the Centre National d’Art et de Culture Georges Pompidou, Paris (1987); and El pensamiento lineal. En torno a la autonomía de la línea a través del dibujo argentino at the Fundación San Telmo, Buenos Aires (1989).

During the period, Guy Schraenen continued to play an important role in the publication and communication of her work. He invited the artist to take part in a number of projects in Belgium, among them Je est un autre at the Galerij van de Akademie, Waasmunster (1986); Kunst Enaars Publikaties at the Centrale Bibliotheek Rijksuniversiteit, Ghent (1988); Mirtha Dermisache at the Archive Space, Archive for Small Press & Communication (ASPC)46, Antwerp (1989); Kunstenaarsboeken at the Provinciaal Museum Hasselt; Van Boek Tot Beeld at the Cultuur- en ontmoetingscentrum de Warande; and Livres d’artistes at the Provinciaal Museum Hasselt (1990).

In the early nineties, Héctor Libertella made reference to Dermisache’s work in his study of the death of linguistics and the limits of pure orality or pure graphism. Regarding Diario 1 Año 1, he stated:

On the basis of a declared act of written communication, she empties out the receptor’s classical expectations by means of an operation that takes the medium apart, showing it as the issue zero of what a newspaper might have been, and taking the bases of her work—the use of graphism—to its limit: zero function, embryo, mockup of a newspaper, which means mockup of language conceived as an element only possible in relation to communication47.

Later, in 2000, Diario 1 Año 1 was used as the back cover of Libertella’s book El árbol de Saussure. Una utopía48; in 2006, he published La arquitectura del fantasma. Una autobiografía49, and printed a set of graphisms entitled “Mirtha Dermisache lee a Libertella” [Mirtha Dermisache reads Libertella] and “Libertella lee a Mirtha Dermisache” [Libertella reads Mirtha Dermisache]50. He describes Mirtha’s writing as work organized on the sole basis of “a-semantic graphism,” which he—like Arturo Carrera— considers “legible insofar as practice that disregards knowledge, and illegible insofar as ‘result of the visibility’ of thought”51.

In 1992, the tAC regained its former strength as it expanded and brought in new coordinators. On her time away from the tAC and later return, Mirtha wrote the following letter:

Hello! I’m sending this letter to everyone who was involved in my studio at some time… when we were putting together the “taller de Acciones Creativas, de Mirtha Dermisache y otros.” We spent ten years fostering free expression in adults in the visual arts on both individual and group levels—and even on a mass scale when, with all of your help, I held the various editions of the “Jornadas del Color y de la Forma.”

The work we began in 1972, when no one was using this method with adults, came to an end with the closing of my studio in ’82. That period was followed by a time of reflection and rest, and of inner work, a time I spent mulling over other ideas in the sphere of art education.

The reason I am writing to you today is to tell you that I have relaunched the t.A.C. (located, once again, on the upper floor of an old mansion, this time near the corner of Cerviño and Ugarteche streets, in Palermo); the crux of the work will, of course, be essentially the same as it has been since the beginning.

This time, though, I will coordinate all of the classes myself; there will be both individual and group options. At the same time, drawing and printmaking teachers will be available to anyone who wants to investigate those specific techniques.

The idea is to further pursue one’s own path, one’s own graphic world.

Available as well is a children’s studio; its style is like the other studio, but emphasis is placed on painting…

If you want more information, if the project interests you, or if you simply want to come by and see my new space, give me a call… It will be a pleasure, as always, to get together and talk again.

In any case, I send my greetings out to you all after all this time.

Love, Mirtha Dermisache

Taller de Acciones Creativas52

As part of the expansion of activities with the “new” tAC, different guest teachers gave theoretical and hands-on seminars; in November 1993, the “Mirtha Dermisache & otros, taller de Acciones Creativas. IV Encuentro Caminos de Crecimiento” was held at the Centro Cultural General San Martín, an event also geared to furthering creative capacity53.

In 1994, Arturo Carrera published “Las niñas que nacieron peinadas,” an essay in which he analyzes work by Oliverio Girondo and Antonio Edgardo Vigo, as well as Dermisache’s illegible writing. He states:

Writing. Voluminous graphs. Black on white or white on black. This serenely illegible writing suggests a “form” of “visible” thought; its spongy silence goads us toward writing itself, its secret state of stability54.

In 1995, Mirtha republished her Diario 1 Año 1 twice: in facsimile form in Artinf journal and, later, a fifth edition that the artist produced personally for the show Mirtha Dermisache at Galería de Arte Bookstore in Buenos Aires. A roundtable in which Arturo Carrera, Silvia de Ambrosini, Roberto Elía, and Eduardo Stupía participated was held in the context of the show55. That same year, she produced another series of textos ilegibles [illegible texts], a body of work she would continue to explore until approximately 2006. She took part in group shows organized by Schraenen in Germany and in France.

Notes

45 Program: Friday: screening of Sextas Jornadas del Color y de la Forma, a short sound and color film in Super 8 by Carlos Garciarena; roundtable—broadcast live on VCR monitors— coordinated by Emilio Stevanovich with the participation of Jorge Romero Brest, Gregorio Klimovsky, Silvia Puente, and Emilio Renart; exhibition of photographs by Antonio Zaera. Friday to Sunday: screening of the short film by Carlos Garciarena. Screening in loop of a video on the Jornadas by Carlos Dulitzky. Tape of the roundtable. Saturdays and Sundays: workshop using some of the Jornada’s techniques to get a direct sense of the experience; promotion of attendance by media figures.

46 Archive for Small Press & Communication (ASPC) was a center for the documentation, conservation, and exhibition of artists’ publications founded in Belgium by Guy Schraenen in 1974.

47 Libertella, Héctor, “La muerte lingüística,” in Ensayos o pruebas sobre una red hermenéutica, Buenos Aires, Grupo Editor Latinoamericano, Escritura de Hoy collection, 1990, p. 24.

48 Libertella, Héctor, El árbol de Saussure. Una utopía, Buenos Aires, Adriana Hidalgo Editora, 2000.

49 Libertella, Héctor, La arquitectura del fantasma. Una autobiografía, Buenos Aires, Santiago Arcos Editor, 2006.

50 Libertella, Héctor, “Mirtha Dermisache lee a Libertella,” in La arquitectura del fantasma. Una autobiografía, chapter “Lo que se cifra en el nombre,” op. cit., pp. 70–71.

51 Libertella, Héctor, “La muerte lingüística, Los límites de la pura oralidad y Los límites del puro grafismo,” in Ensayos o pruebas sobre una red hermenéutica, op. cit., p. 31.

52 Letter from Mirtha Dermisache, taller de Acciones Creativas, n.d.

53 The coordinators were Alicia Machta, Armando D’Angelo, Adriana Alesanco, Eugenia Cudisevici, Clarisa Szuszan, Natalia Kazah, Maya Ballen, Silvia Gennaro, Sandra Plitt, Ivana Martínez Vollaro, and Lucía Cardin.

54 Carrera, Arturo, “Las niñas que nacieron peinadas,” Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos, no. 529/30, July–August 1994, n.p. (http://bibliotecadigital.aecid.es/bibliodig/es/catalogo_imagenes/imagen.cmd?path=1005722&posicion=1®istrardownload=1).

55 For further information, see Carrera, Arturo, “Sobre signos y esencias,” Artinf journal, Noticias de Aquí y Allá section, Buenos Aires, year 19, no. 92, spring 1995, p. 42.

1998-2011Multiple writings and public readings

Musical selection for this episode

Schumann / Grieg, Piano Concertos, Berlin Philharmonic, conducted by Krystian Zimerman

Bach, Air and other orchestral suites, Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Karl Münchinger

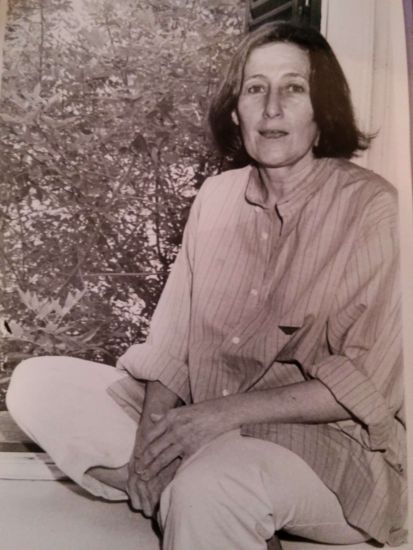

Starting in 1997, Mirtha returned to her work with renewed vigor. She produced books and illegible texts with new graphisms and attempted to return to some of her graphic production from the seventies. She also created more notebooks56.

In 1998, she produced two books and a great many postcards, as well as matrices for possible future editions. In 1998 and 1999, she took part in group projects geared to legitimizing the artist book as art form, events like Libros de artistas III, curated by Juliano Borobio Mathus, Enrique Horacio Gené, and Pedro Roth, Biblioteca Nacional, Buenos Aires; Books from the End of the World. Artists’s Books from Argentine in Philadelphia, Foundation for Today’s Art/NEXUS; Libro de artista, Fundación Telefónica, Chile; Libros de artistas IV, Museo Eduardo Sívori, Buenos Aires; and Studienzentrum für Künstlerpublikationen, Neues Museum Weserburg Bremen. Two exhibitions held in Mexico and curated by Martha Hellion—Ulises Carrión’s wife—evidence not only the couple’s interest in Mirtha’s work, but also their determination to disseminate the artist’s book genre and its universe in Europe and Latin America. The shows were El arte de los libros de artistas, held at the Instituto de Artes Gráficas de Oaxaca and at the Biblioteca Francisco de Burgoa del Centro Cultural Santo Domingo, Oaxaca, Mexico (1998); and Ulises Carrión. Cuatro Décadas. El arte de los libros de artistas, held at the Biblioteca de México, Mexico City, Mexico (1999). Also in 1999, she produced tarjetones [large cards], works in a format somewhat larger than her postcards, and brought an entirely new format, the newsletter, into her production. She published one of her postcards in Artinf and produced 7 Tarjetas postales [7 Postcards], a set of seven works, each with a large print run; for each model, there were seven signed original copies. The conception, first insinuated in Cahier nº 1, was akin to the idea of the “split edition” that the artist would later develop.

The book Andes57, by Juan Carlos Romero, was the culmination of a collective publication project on which Mirtha worked. At the dawn of the new century, she participated in a number of group shows in Buenos Aires, among them Siglo XX argentino. Arte y cultura, Centro Cultural Recoleta (1999–2000); Libros de artista, Arcimboldo gallery (2000); Instantes gráficos. El libro de artista, Fundación Rozemblum (2001), and Palabras perdidas. Escrituras y caligrafías en el arte argentino (2001), Centro Cultural Recoleta. Fellow participants in that last show included Ernesto Deira, León Ferrari, and other contemporary artists who together interrogated the meaning of the relationship between word and image, or the loss of meaning in the space between them; the works on exhibit made use of an array of formats (paper, canvas, object, installation, video, etc.). At the same time, Mirtha took part in an edition of stamps organized by Vórtice Argentina for the “Día del Arte Correo,” an event held at the Palacio Central del Correo Argentino.

She continued to show work in exhibitions abroad, among them Out of Print. An Archives Artistic Concept, held in Belgium, France, Spain, Slovenia, Croatia, Portugal, and Germany (2001), and Verlage-wie keine anderen / Publishers as No Others, Teil 5, Eine Ausstellung (2002), both curated by Schraenen; she participated in Outside of a Dog. Paperbacks and Other Books by Artists, curated by Clive Phillpot for the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead (2003–2004). In Buenos Aires, her work was featured in group shows like Las camitas at the Centro Cultural Recoleta (2002–2003), where five hundred artists were given a small metal bed on which to intervene. Proceeds from the show, which was organized by the Asociación de Artistas Visuales de la República Argentina (AAVRA)—members included artists Elda Cerrato, Diana Dowek, Margarita Paksa, Nora Correas, Ana Maldonado, Leo Vinci, Ricardo Longhini, and Marcelo Cofone—went to help the Hospital Paroissien in La Matanza, a working-class Buenos Aires neighborhood, buy medical supplies. Mirtha used the opportunity to apply the concept of por sumatoria (by summation): she invited thirty-three artists to do interventions on the bed’s small sheets. The printer Latingráfica joined the effort, printing five hundred postcards with images of bed-works; the postcards were also for sale as a means to raise funds. In these years, Mirtha’s work was featured in publication projects like El Surmenage de la Muerta58 and “Página de Artista,” the section of the Diario de Poesía that Eduardo Stupía, the journal’s art director, coordinated59.

In 2003, three events affected the course of the artist’s graphic production and the visibility of her work in Buenos Aires—a context where Mirtha was largely forgotten. First, she wrote two books—her last bound, titled, and signed works in that format. Second, she came into contact with Geneviève Chevalier, Florent Fajole60, and Jorge Santiago Perednik, editors with whom Mirtha worked to create new formats that challenged traditional forms of publication and exhibition. Together, they produced Libro Nº 8, 1970 [Book No. 8, 1970] (2003), where the information about the edition is located on a sticker attached to the plastic covering around the book, letting the reader choose whether to keep the device or to throw it away. They also presented Libro Nº 1, 2003 [Book No. 1, 2003], where the concept of the “split edition”—a format that included an original sheet between copies—was introduced. In 2004, they published Nueve newsletters & un reportaje [Nine Newsletters & an Interview] (1999–2000), occasion for Mirtha’s first solo show in Argentina. Entitled Mirtha Dermisache. Escrituras [:] Múltiples, the show was held at El Borde Arte Contemporáneo gallery and curated by Olga Martínez, the gallery’s director. It was in that context that the “editorial device” emerged as concept and exhibition format. Fajole recalls:

In 2004, Olga Martínez approached Mirtha Dermisache about holding a show … Rather than put together a traditional exhibition, she arranged a common print run of four hundred copies on ten tables, one for each of the works published; there were twelve chairs that could be moved around.

In attempting to describe this form of installation, I associated the words device and editorial. Device because tied to both the act of laying out and the publication as object. Like any other publication, this one is a space-time configuration that circulates in a defined context. [I chose] the word editorial, meanwhile, because it is not a question of exhibiting originals but rather of witnessing the final stage of the work’s production.

This protocol also means that the reader can be directly engaged in the end of the work’s process. People can circulate freely between the tables, take a seat, leaf through the editions, go somewhere else, that is, they reconfigure the edition as they like when they leave the venue with their own selection/edition61.

The only prior publication of her works in the interview format was by Gabriel Levinas in the monthly El Porteño (Buenos Aires, year 1, no. 3, May, second period, El Porteño press). In the same line of production, the newsletter and interview devices were exhibited once again in 2004, in a show curated by Fajole and Nicolas Tardy for the Centre International de Poésie Marseille. The notion of “editorial device” was central to Mirtha’s production in these final years as her work veered towards publications, which had always been her main objective. From 2004 to 2006, she took part in group shows in Argentina, Italy, France, and Portugal. Her newsletters were featured in New Magazine. International Visual and Verbal Communication in 200462; Luna-Park journal published Livre nº 1, 1978 in 200663; issue 10 of OEI was dedicated to her art64.

In 2005, she began to work in the lecturas públicas [public readings] format, which consisted of large columns of text. This was the first of what would be many series of large works, among them textos murales [mural texts] (starting in 2007), instructivos [instructions], and afiches explicativos [explanatory posters], the last of which was envisioned in 2010 as an intervention in the public space65. She and Florent Fajole produced a number of other publications—Lectura pública 1 [Public Reading 1], for instance— on the occasion of solo shows like Mirtha Dermisache. Dispositivo editorial 2. Lectura pública, Centro Cultural de España en Buenos Aires, and Lectura pública 3 [Public Reading 3], featured at a show of the same name at El Borde gallery.

In 2006, the artist, along with Fajole and Guillermo Daghero, published Libro Nº 2, 1968 [Book No. 2, 1968], which was featured in the show Mirtha Dermisache. Editorial Device No. 3, Bookartbookshop, London. In 2007, Fajole published Diez cartas [Ten Letters] as part of the show Mirtha Dermisache. 10 Cartas (y otras escrituras). Dispositivo editorial 4, Instituto Italo-Latino Americano, Rome; in 2008, Libro Nº 2, 1972 [Book No. 2, 1972] was exhibited at Mirtha Dermisache. Livres. Florent Fajole. Dispositif éditorial, a project curated by Didier Mathieu at the Centre des livres d’artistes de Saint-Yrieix-la-Perche.

In 2009, Libro Nº 1, 1972 [Book No. 1, 1972] was exhibited at the Centre d’art Le 19, Crac, Montbéliard, and Diez cartas was re-released in an editorial project coordinated by Olga Martínez.

This time, the letters came with envelopes so that they could be dispatched and, hence, their meanings determined by the sender and the recipient. The group of works is known as Cartas para mandar [Letters to Send]. Pertinent to this production are Mirtha’s words, “I am not trying to say anything. [The work] becomes meaningful when the individual who engages it expresses himself through it"66.

In 2010, the letters were presented by Mercedes Casanegra and Edgardo Cozarinsky at the Centro Cultural de España, Buenos Aires67. At the invitation of Guy Schraenen, Dermisache’s work was featured in group shows: in 2009, at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Barcelona (MACBA), and in 2010, at the Museo de Arte Abstracto Español - Fundación Juan March in Cuenca.

From 2009 to 2011, she took part in two exhibitions that would prove essential to gaining her work greater conceptual, as well as commercial, recognition, and earning it a place on the local and international contemporary art market. The first was the international exhibition elles@centrepompidou. Artistes femmes dans les collections du Musée national d’art moderne, curated by Camille Morineau. Second, a section of the show Sintonías. Elba Bairon, Alejandro Cesarco, Mirtha Dermisache, Esteban Pastorino, Alejandra Seeber dedicated solely to her work; curated by Olga Martínez, that section of the show at Fundación PROA consisted of publications by Mirtha on display in PROA’S bookstore alongside other books—just as the author had always wanted.

As Martínez says:

This is where the work takes on its full meaning, reaching a point where the publication displaces the original—manuscript—to begin its route through the channels of the publishing world. It is as such that in the PROA bookstore the artist’s recent publications will be sold, made available to the visitor to touch, read, and buy, and as such creating a space to link the publication and the viewer/reader68.

After those events, Mirtha’s work was in demand at art fairs; museums wanted her pieces for their collections. It was at this time that Mirtha and Olga Martínez agreed to donate certain works to museums in order to heighten interest in her production and further its dissemination.

In 2010 and 2011, Mirtha, in conjunction with Fajole and Daghero, published Fragmento de historia de 1974 [Story Fragment from 1974], 2010; Texto de 1974 [Text from 1974], 2011; and Cuatro textos [Four Texts], produced between 1970 and 1998. Those final two are limited-edition works made using the “cromopaladio” technique, which, as Florent Fajole explains, is “a mixed photochemical process that sets out to explore a certain dimension of the process by evidencing the gap between reproducing and copying without compromising the quality of the print run in order to create multiple singularities.”69

In 2011, the retrospective Mirtha Dermisache. Publicaciones y dispositivos editoriales, curated by Cecilia Cavanagh, was held at the Pabellón de las Bellas Artes of the Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina (UCA). The show, which explored different phases of Mirtha’s production, was the last one to be held before the artist’s death in January 2012.

Notes

56 Mirtha never exhibited her legible or incomprehensible texts or her notebooks. According to Olga Martínez in an interview with the AMD staff held in Buenos Aires on November 20, 2016, the artist showed her those works only once; “she kept them in secret, hidden from view even in her studio.” The work was first seen when the AMD was organized.

57 Romero, Juan Carlos, Andes, Santiago, Chile/Buenos Aires, p. 7.

58 El Surmenage de la Muerta (San Sartres en artes), Buenos Aires, year 2, no. 6, December 2002, and year 3, no. 7, May 2003. Mirtha’s intervention consisted of replacing a whole page with one of her illegible texts. For issue 7, 2003, she intervened on the cover and other sections by placing illegible texts on them without altering their structure.

59 “Página de Artista,” in Diario de Poesía. Información. Creación. Ensayo, Buenos Aires/ Rosario, quarterly journal, no. 62, December 2002, p. 26, and no. 71, December 2005 to April 2006, pp. 1, 11–20. Mirtha’s intervention, featured among articles by other authors, consisted of her illegible texts and reproductions of the Diario 1 Año 1.

60 French editor Florent Fajole came to Buenos Aires at the beginning of the new milennium; he first saw Mirtha Dermisache and Horacio Zabala’s work at the Abraham Vigo Archive.

61 Fajole, Florent, “El trabajo de Mirtha Dermisache editado por Florent Fajole. Aspectos de una relación creativa,” article in the AMD, n. d.

62 New Magazine. International Visual and Verbal Communication, Belgium, no. 1, August 2004, pp. 124–135.

63 “Livre nº 1, 1978,” in Luna-Park, Paris, no. 3, Nouvelle série, fall, pp. 153–173.

64 “Mirtha Dermisache,” in OEI, Marseille, éditions du VELO, no. 10, October 2006.

65 Rimmaudo, Annalisa and Lamoni, Giulia, op. cit., p. 12.

66 Quoted in Jorge Glusberg, “Organización y proyecto de arte de sistema,” in Artinf, Buenos Aires, year 17, no. 86, 1993. Special issue on the Bauhaus.

67 For a video of the presentation, see http://www.cceba.org.ar/v3/ficha.php?id=62#modulo171

68 Martínez, Olga, Más allá de la escritura, Buenos Aires, Fundación PROA, 2010. (Available at http://www.proa.org/esp/exhibition-sintoniasmirtha-dermisache-1.php#1).

69 Fajole, Florent, op. cit., n.p.

Mirtha after Mirtha

To be read in silence

Mirtha Dermisache died on January 23, 2012. Her final work was left on her drawing table and inspirational phrases on her blackboard as efforts to organize her archive got underway.

Five years later, French critic Philippe Cyroulnik, editor of the five hundred explanatory posters for the show PLC Punto, línea y curva (Centro Cultural Borges, 2011), explained:

It is thanks to the subtlety and rigor of her writing with no words, her typography with no texts, and her drawings with no images that Mirtha Dermisache is a crucial figure not only in Argentine art, but in what is known around the world as visual poetry.70

In 2012, she was awarded the Premio Konex a las Artes Visuales71, and in 2013 work on cataloguing her art and organizing her archive—now the Archivo Mirtha Dermisache (AMD)—began. Alejandro Larumbe, the artist’s nephew, explains:

As her nephews, creating the archive is a way of honoring our extremely talented aunt in order to enable her work to be seen around the world and to live on. We feel that her graphisms are a message to humanity; it is not until a person beholds them that they take on meaning in a highly personal and free process of re-creation. The archive is a way of recognizing a life of steadfast and inspiring work.72

Mirtha Dermisache’s work continues to gain prestige in Argentina and beyond. Curators and artists have requested it on loan for a range of projects. Her art, now represented by the Henrique Faria gallery in Buenos Aires and New York, has been featured in exhibitions and art fairs such as Solo Project at ARCO in 2014, where she also represented Argentina in 2017. In 2014, her work was included in the group show Drawing Time, Reading Time held at the Drawing Center in New York; it was with that show that the AMD began enacting its loan policy as part of its mission. In 2015, the process of cataloguing and organizing the AMD was completed. In 2016, her work was featured prominently in the show Poéticas oblicuas. Poesía concreta, escritura automática, conceptualismo, curated by Fernando Davis and Juan Carlos Romero for Fundación OSDE.

By way of closing and farewell, Leonor Cantarelli, Mirtha’s friend and executor of her will, reflects:

Mirtha and I were bound by a friendship as strong as it was mysterious. Our lives were not always in synch and our tastes not always the same. But we were always tied by humor—I liked making her laugh. Like her graphisms, she was delicate and her taste exquisite, but austere. She was a creature of rituals, from the way she would make coffee and herbal teas to the way she would set the table, prepare techniques for her students, welcome them and bid them farewell at her studio classes. She loved technology, but she was always afraid of losing data, passwords, and archives, which is why she carefully wrote down the steps to access them in her notebooks and calendars. Every situation was, for her, worthy of respect and care. Mirtha was a fragile person; what moved her was the desire to help others. She didn’t seem made for this world…73

Notes

70 Quote in María Paula Zacharías, “Mirtha Dermisache. La esencia de la escritura”, La Nación newspaper, Sunday, January 15, 2017. (Available at http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1975292-mirtha-dermisache-la-esencia-de-laescritura).

71 Diploma al Mérito. Arte Conceptual: Quinquenio 2002-2006; Fundación Konex, Buenos Aires.

72 Interview by the AMD staff with Alejandro Larumbe, Buenos Aires, March 12, 2016.

73 Interview by the AMD staff with Leonor Cantarelli, Buenos Aires, October 17, 2015.